Track List

- Part One

- 8:07

- Part Two

- 9:41

- Part Three

- 15:45

- Part Four

- 8:37

- Part Five

- 9:32

- Part One

- 8:55

- Part Two

- 14:46

- Part Three

- 4:10

- Part Four

- 7:23

“At 83, Rivers rises to the occasion with a sustained power that would be remarkable coming from an artist half his age. Considering how few albums this trio recorded during its time together … Reunion is an unexpected gift.” – [Jazz Times], Lloyd Sachs

“The two improvised sets they played were marvelous, picking right up where they left off in 1978 – strong, swinging, and incisive, with not a hint of hesitation or tentativeness.” -[Chicago Reader], Peter Margasak

“In two nonstop, fully improvised sets, Rivers who died in 2011 immediately draws the ear here with a fluid and ever-evolving sort of movement on saxophone, flute and even piano. But it’s the interplay that can take your breath away.” -[LA Times], Chris Barton

“The music they created compares quite favorably to what fortunate audiences heard them play back in the day at Studio Rivbea.” -[JazzTimes], Scott Albin

“The trio glides effortlessly between bebop passages, tonal and atonal breaks and some passionate soloing. Rivers switches between tenor and soprano saxophones, flute and piano, each with its own personality. His tenor paints wide splotches of sound, while his soprano cuts more precise channels. On flute he pops and floats, and his piano sound is informed by a more charming Cecil Taylor. Where Holland’s current ensembles featured his organization, here he is freed up to explore without a map. He takes several solos, passages unexpected yet built like a hurricane-proofed structure.” -[All About Jazz], Mark Corroto

“…the reunited trio confirms how varied and coherent free improvising can be. Its music provides a reminder of why folks sometimes call such endeavors “instant composing.” Rivers preached and practiced the idea that playing “free” meant free to include anything you could play loud or quiet, lyrical or fragmented, tonal or atonal, flamenco or the blues. — Improvising groups that play together a lot may develop informal routines or reliable ways to get the music moving. They may never discuss them, but they silently agree that they work. Rivers’ trio is one of the great examples, as Rivers always milked the contrasts among his burly tenor and sinewy soprano saxophones, his sketchbook-y piano and that willowy flute that could sound eerily like his speaking voice. Holland and Altschul laid down all manner of supportive patterns for Rivers to roam over vamps and bridgework for all moods and tempos. — He may have been right about the recognition, but this much is certain: Rivers’ ’70s trios this one especially pointed out a full range of possibilities to many freewheeling combos that came later.” -[NPR], Kevin Whitehead

>”The 90 minutes of music here (all improvised) vibrate with an intensity, freedom and unspoken connection that recollects the loft scene’s ’70s glory without explicitly referencing it. The recording quality is unimpeachable, but what is far more interesting is how these players’ approaches to music have evolved over three decades without losing their essential magic.” -[Orlando Weekly], Jason Ferguson

>”Just about everything released on this independent label is of interest to aficionados of the outward bound, and this is a particularly rewarding documentation of a fearless woodwind giant (Rivers) getting his ’70s trio back together for one last gig. No set list, just three veterans listening to and daring one another onstage. Rivers played on a seemingly infinite number of recordings, particularly later in his long career, but this one should stand out for its brave sonic poetry as well as its top-notch rhythm section.” -[Denver Post], Bret Saunders

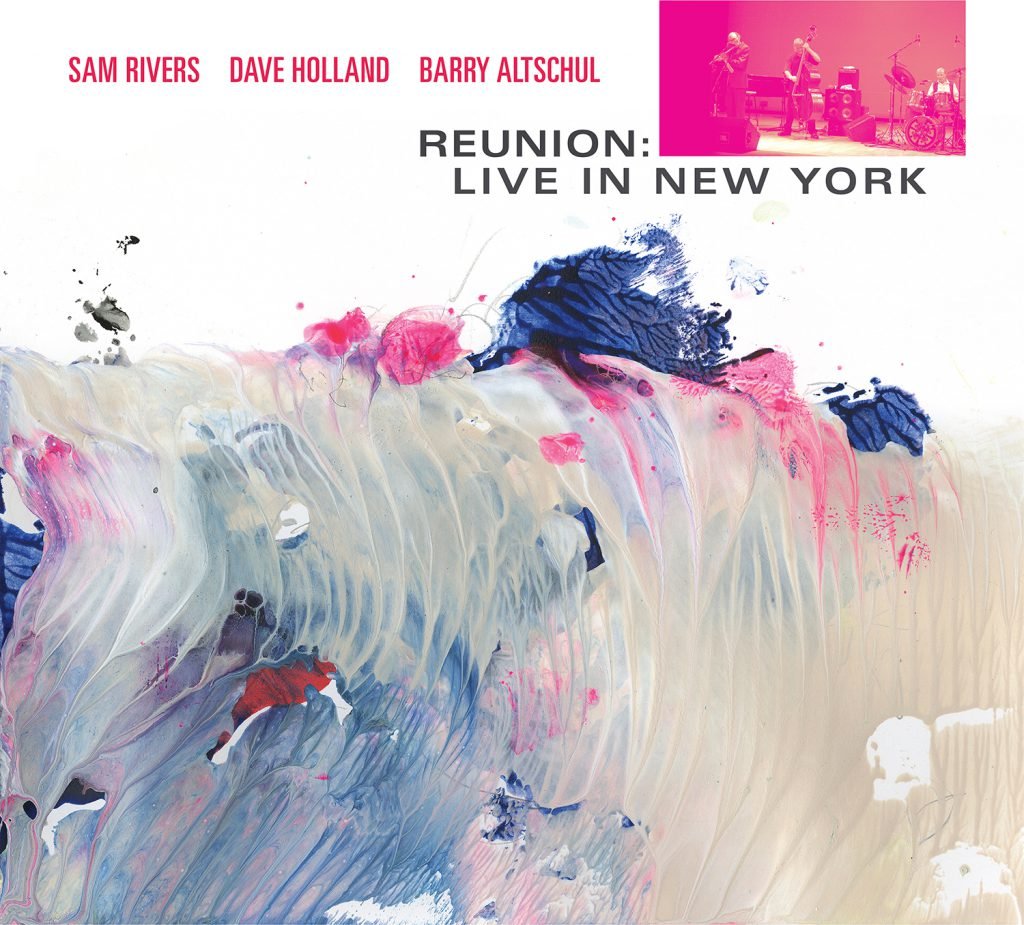

A historically important new release, Reunion: Live in New York captures saxophonist/flutist/pianist Sam Rivers with his groundbreaking trio of Dave Holland on bass and Barry Altschul on drums recorded live in front of a packed Miller Theatre at Columbia University in 2007. The trio was influential for helping lead the movement towards free form playing on the loft jazz scene in the 1970s. Over two sets, their powerful rapport in these fully-improvised performances gives no clue that they had not played together in 25 years when this concert took place.

The release coincides with what would have been Sam Rivers’ 89th birthday; he passed away on December 26, 2011. A leading figure in jazz, Rivers led a remarkable assortment of aggregations, from the small groups on his four classic albums on Blue Note in the 1960s to duos to big bands over the following decades. He also played in the bands of such luminaries as Miles Davis, Andrew Hill, Cecil Taylor and Dizzy Gillespie and his composition Beatrice is a standard in the jazz repertory. His big band albums Inspiration and Culmination from 1998 were both nominated for the Grammys.

It would be hard, though, to overstate another important role that Rivers played in jazz: He was the founder and proprietor of Studio Rivbea, the most prominent of the many jazz lofts that sprung up in downtown Manhattan in the 1970s that encouraged a more open approach to the music. Rivbea began hosting concerts, workshops, and rehearsals in 1972, just as Rivers-Holland-Altschul began playing together intensively. Other bassists and drummers played with Rivers, but they were the preferred formation from the fall of 1972 when Holland joined the group until the summer of 1978 when Altschul left to pursue his own projects as a bandleader.

The trio also became the main vehicle for what Rivers often called his “main contribution to the music”: the exploration of free-form playing. In a 2002 interview, he explained that by free he “did not mean avant-garde or atonal, but instead that there was no preconceived idea, no preconceived melodies or harmonic attitude.” Rivers sometimes went so far as to claim to have originated this approach. As Holland puts it, “each night we started with a blank page.” According to Altschul, they developed what became an almost extrasensory attunement to each other through extended jam sessions: “We got together let’s say at eleven o’clock in the morning and we just played until five o’clock in the afternoon. If we had to go to the bathroom, then it was a duo. If we had to eat, there was maybe a solo. But the music continued from eleven to five. The aim was not only to become familiar with each other, but also to find and play through the dead spaces in the music, to concoct tactics for avoiding them in performance.” “After a while,” Rivers noted, “you’ve run through all your clichés.” The group became known for its marathon concerts, with Rivers circulating among tenor and soprano saxophones, flute and piano, giving each performance the feeling of a suite with shifting dynamics among the players.

What separates this trio from some of the more incendiary exemplars of 1960s free jazz is the sense that nothing is out of bounds: there are moments of thorny dissonance, but also currents of limpid melody, and moments where a tonal center shimmers into view or the music locks into a groove. As Altschul points out, “freedom means above all freedom of choice among any number of stylistic parameters at any moment in performance.” In the late 1990s, Holland remarked that he was “struck by the way Rivers uses all his musical experience when he plays, from the blues to bebop to the more harmonically venturous elements of his own music” and he never forgot something Rivers said to him: “Don’t leave anything out: play all of it.” Rivers called the 1970s “a culmination of the previous decades, and the trio in this sense was an enactment of the somewhat idealistic but thrilling notion that improvisers working at the height of their powers can draw on a total access to all musical elements.”

The special reunion concert was the culmination of Columbia University radio station WKCR’s week-long Sam Rivers Festival, which was breathtaking in its sustained focus, as in-depth interviews with Rivers and many of his key collaborators were interspersed within a chronological review of his legacy: over a full week, day and night, the station played every recording of Rivers it could obtain, including not only commercial sessions but also unreleased concert tapes. The broadcast served to demonstrate in stunning fashion the breadth of Rivers’s musical world.

The highly anticipated concert drew a sold-out audience seemingly packed with a who’s who in jazz in New York City. There was no rehearsal other than a ten-minute sound check prior to the performance and, true to form, there was no prior discussion of what they would play. Rivers started with a figure on tenor sax and Holland and Altschul quickly fell in behind him. Off they went for the next hour on an extemporaneous journey, conjuring the decades-old magic.

Although the trio performed extensively, it is surprising how poorly it was documented on record. Aside from two small-label European releases, The Quest (1976) and Paragon (1977), the best-known artifact of their playing together remains Holland’s first album as a leader, the exquisite Conference of the Birds (1972), which memorably pairs Rivers with Anthony Braxton. But Holland’s album was recorded right at the inception of the trio, and cannot be called representative of what its sound would become. In other words, the concert on this release is not only an all-star reunion, but also one of the very few documents of one of the great groups of the 1970s.

The drama of any improvised performance has to do with the impression that one is witnessing a conversation unfolding in the moment, with the emotional tides and fleeting resolutions in any human interaction. There is an uncommon, audibly joyous intimacy audible in this concert as the trio steps back onto the tightrope one more time. The thrill they rediscover is not only a fitting testament to the giant that was Sam Rivers, but also the best memorial to the Rivbea environment that only his vision could have brought together.